Margaret Sarah Carpenter

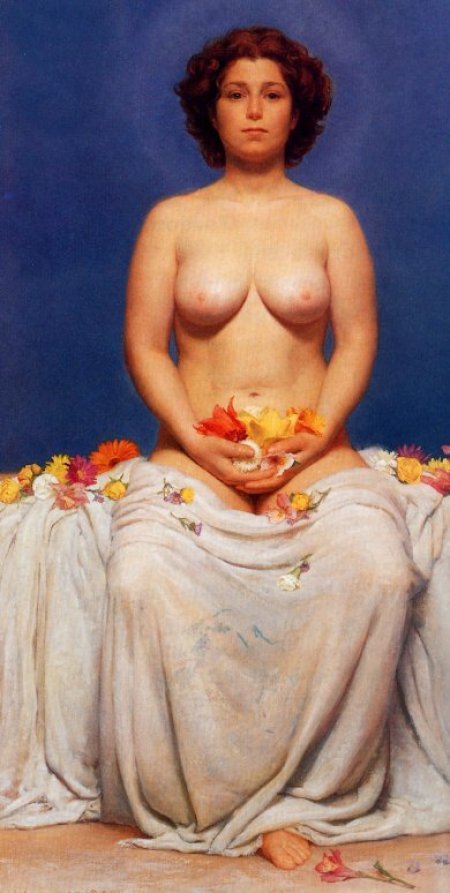

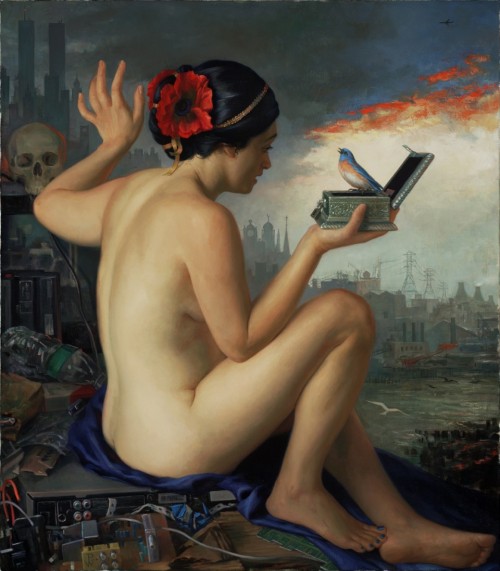

Margaret Sarah Carpenter (Salisbury 1793 – 13 November 1872 London), born Margaret Sarah Geddes, was a British Late Romantic/Victorian painter. She was especially noted for her portraits. Her portraits follow in the tradition of Sir Thomas Lawrence, but tend to be more fanciful and feminine character… particularly her portraits of children. Carpenter’s portrait of her sister, Henrietta (above) is especially delicious… and clearly rooted in the manner of Rembrandt.

-Portrait of Harriet, Countess of Howe

-Portrait of Maria Stella Petronilla

-John Bird Sumner

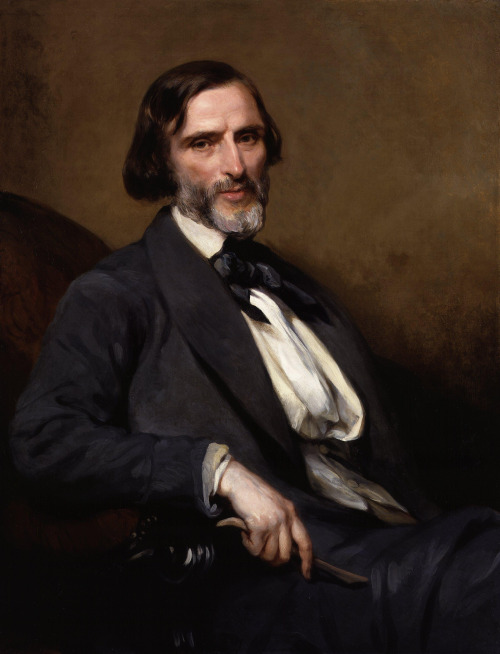

-Portrait of John Gibson

-Portrait of Mr. Bird and his Wife

-Young Girl with a Dog

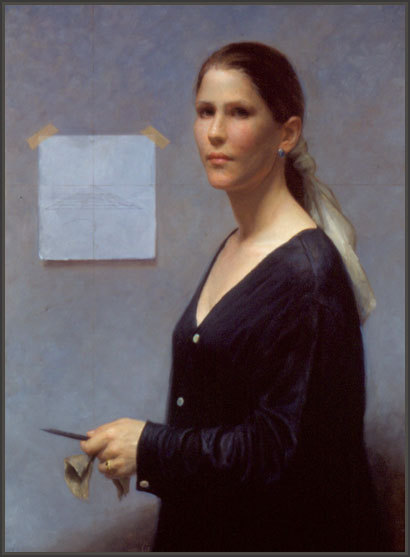

Margaret Sarah Carpenter was born in Salisbury, the daughter of Captain Alexander Geddes and Harriet Easton. She was taught art by a local drawing-master. In 1812, one of her copies of the head of a boy was awarded a medal by the Society of Arts, and she was awarded another medal in 1813, and a gold medal in 1814. That year, she moved to London and soon established her reputation as a fashionable portrait painter. She exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy between 1818 and 1866. She also exhibited at the British Institution and at the Suffolk Street Gallery. Three of her works are in the National Portrait Gallery of Britain, including portraits of her husband, her close friend, the artist Richard Parkes Bonington, and John Gibson, R.A.

-Mrs. Charles Saline Thellusson

-Portrait of Richard Parkes Bonington

-Study of Henrietta Baillie

-Ada Lovelace

-Ada Lovelace (detail)

-Portrait of Mrs. Simpson

Margaret Sarah Carpenter married William Hookham Carpenter, Keeper of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum. Their children included two noted painters, William and Percy Carpenter. Margaret introduced her sister Harriet to the young painter William Collins. They eventually married, making Margaret the aunt to the author, William Wilkie Collins. Upon the death of her husband in 1866, she was given an annual pension of £100 by Queen Victoria… partially based on her husband’s service, but also in recognition of her own artistic merits. She died in London at age 80.

-George Warren, Second Lord Tabley

-Henrietta Shuckburgh

-Lady Fitzwygram

-The Gleaner

-Mary, Lady Haddo

- Eleonora Long, née Montagu

-Belinda Way

-Miss Theobald

-Portrait of William Hookham Carpenter, the Artist’s Husband